ARC Ensemble

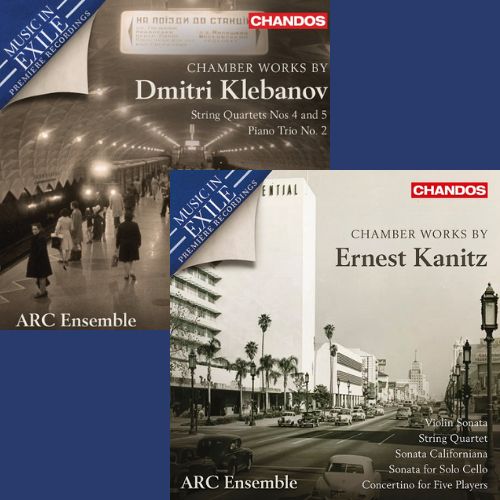

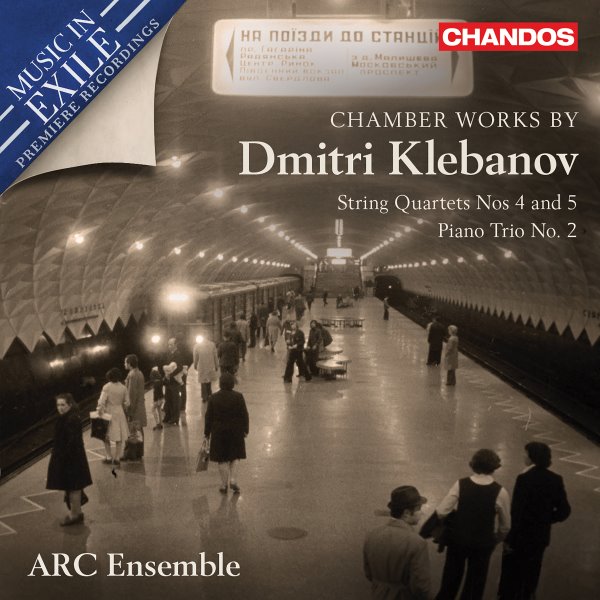

Chandos Records Ltd – Collection Music in Exile

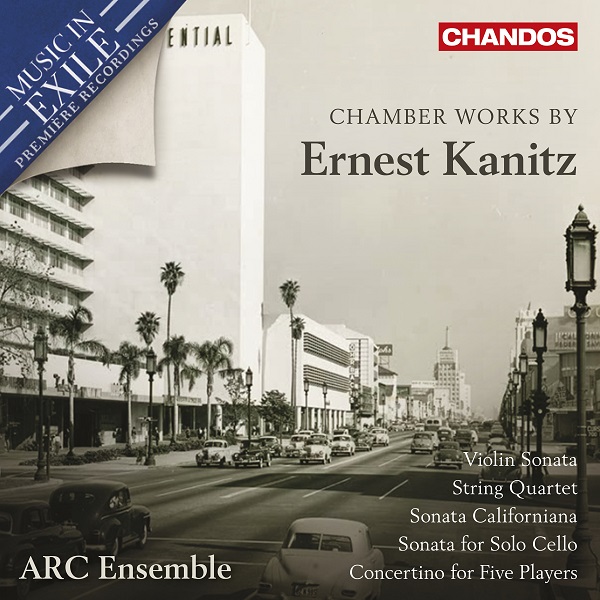

The fifth and ninth releases in the “Music in Exile” collection, Chamber Works by Dmitri Klebanov and Chamber Works by Ernest Kanitz, released by Chandos in 2021 and 2025, introduce us to the unjustly forgotten works of two Jewish composers, one Ukrainian and one Austrian, who were victims of 20th-century totalitarianism.

As with each volume in the Music in Exile collection, the fate of these two composers is amply documented in the booklets by Simon Wynberg, director of the ARC Ensemble (Artists of The Royal Conservatory), founded in 2002 and based in Canada.

Dmitri Klebanov (1907-1987)

Born in Kharkiv on July 25, 1907, into a family with little interest in music, Dimitri began taking violin lessons at the age of six and gave his first recital a year later. He also developed a passion for the piano, improvising for hours on end. At the Kharkiv School of Music, Klebanov was the youngest student in his class. In 1923, he was admitted to the Institute of Music and Dramatic Arts, where he studied under the pedagogue and composer Semion Bogatyrev. By the end of his studies in 1926, at the age of just 19, Klebanov had already composed two string quartets, a piano trio, several short instrumental pieces, and a number of melodies, works that were undoubtedly lost or destroyed during World War II. In 1927, he was hired as a violist by the Leningrad Opera Orchestra.

Back in Kharkiv, Klebanov worked with Herman Adler, principal conductor of the Ukrainian State Orchestra in the mid-1930s. He then conducted the Kharkiv Radio Orchestra, as well as various dramatic productions. In 1939, the Bolshoi produced the children’s ballet Aistenok (Little Stork), based on his opera of the same name. This was followed by a second ballet, Svetlana, again aimed at a young audience, which featured Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Tatar dances. His Violin Concerto No. 1 was premiered in 1940, the year he married Nina Diakovskaia, who was then director of the Kharkiv State Conservatory.

In June 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union, Klebanov was among the 150,000 Jewish refugees evacuated to Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Among them were many artists, such as the young Polish composer Mieczysław Weinberg, the actor Solomon Mikhoels, the writer Nadezhda Mandelstam, and the poet Anna Akhmatova. In Tashkent, Klebanov taught and composed music for both theater and cinema.

In November 1943, Soviet forces recaptured Kiev and the retreating Wehrmacht set fire to the already badly damaged city. Back in Ukraine, Dimitri, Nina, and their newborn son, Yuri, spent several months in the city, forced to live in a rat-infested basement until May 1945, when they were finally able to return to Kharkiv. In Kharkiv, Klebanov began work on his First Symphony, which he dedicated “To the memory of the martyrs of Babi Yar,” the infamous ravine in Kiev where, over two days at the end of September 1941, nearly 34,000 Jews were murdered. This symphony premiered in Kharkiv in 1947, as part of a concert entirely devoted to Klebanov’s music, including his Violin Concerto No. 1 and the Welcome Overture.

The enthusiastic reception given to this symphony led to further performances in Kharkiv and Kiev, but problems arose in 1949 when it was submitted for the Stalin Prize. The commemoration of Jewish rather than Soviet victims, evidenced in particular by the use of traditional Jewish melodies and biblical cantillation, was condemned as “insolent” and unpatriotic. Further performances were banned and Klebanov was denounced as a “bourgeois nationalist” and a “rootless cosmopolitan” (the hackneyed euphemism for Jews). Nina immediately left for Moscow to plead her husband’s case. Before the war, she had been director of the Opera Studio at the Moscow Conservatory and was then director of the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture. Her status undoubtedly gave weight to her pleas, and Klebanov was neither imprisoned nor deported. However, this episode plunged him into anxiety and anguish, a state familiar to many Soviet artists of the time. He then entered into internal exile, forcing himself to restrict his creative abilities and aesthetic ambitions in accordance with the directives of the Soviet authorities. His Piano Quintet, for example, composed in 1954, was commissioned to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Pereyaslav, by which Russia took control of Ukraine. The Soviet Union marks this so-called “great Ukrainian-Russian alliance” with extravagant national celebrations, which an Ukrainian loyalist like Klebanov must find both artificial and uncomfortable. His contribution will be a quintet as grandiloquent as it is predictable.

Klebanov’s professional rehabilitation began during the Khrushchev era. In 1960, the Kharkiv Institute appointed him associate professor. Ten years later, he was promoted to principal professor of composition and orchestration and taught a generation of Ukrainian composers, including Viktor Sousline, Valentin Bibik, Vitali Houbarenko, Marc Karminski, Boris Jarominski, and Vladimir Zolotoukhine. In 1966, Klebanov was a member of the jury for the Tchaikovsky Competition chaired by violinist David Oistrakh, and the following year he was proclaimed “Honored Artist of Ukraine.” In 1968, the Central Committee of Ukraine offered Klebanov the position of director of the Union of Ukrainian Composers. This position required him to move to Kiev, where his career had begun to decline, and the offer came with an unacceptable condition: Klebanov had to join the Communist Party. He refused categorically, just as he had never agreed to associate his name with denunciations of dissidents and critics of the regime.

In the mid-1980s, when Klebanov was already a well-known composer in Ukraine, he got a commission for a concerto for viola and Japanese Silhouettes, a piece for soprano, viola d’amore, and orchestra. These two pieces are the only ones to have been commercially released in the West, although the Soviet label Melodiya recorded several of his works and Ukrainian Radio often broadcast his music during the 1960s and 1970s. During this same period, several conductors asked him for permission to perform his Symphony No. 1, dedicated to the martyrs of Babi Yar, but Klebanov was adamant that its next performance should be posthumous. It was finally performed again in 1990, some three years after his death on June 6, 1987.

Klebanov’s catalog of works includes nine symphonies, several chamber music pieces, two violin concertos and two cello concertos, various pieces for violin and piano, operas, ballets, around a hundred songs (most of which remain unpublished), and nearly twenty film scores. He also published two important theoretical works in Kiev in 1972, The Art of Instrumentation and The Aesthetic Foundations of Instrumentation.

Sources: © 2021 Simon Wynberg – CD booklet Chamber Works by Dmitri Klebanov

Ernest Kanitz (1894-1978)

In many ways, Ernest Kanitz’s career path was similar to that of other composers in the “Music in Exile” collection. Born on April 9, 1894, into a wealthy Jewish family in Vienna, Ernest Kanitz was encouraged by his mother, a pianist, to pursue music. He began taking piano lessons at the age of seven and started composing the following year. During his adolescence, he worked with Richard Heuberger, a famous critic and composer with a passion for choral music, and later with Franz Schreker, arguably the most influential composer-teacher in Europe.

In 1920, he married Gertrud Reif, an accomplished pianist who had attended Arnold Schönberg’s composition seminars. In 1922, he was appointed professor of harmony, counterpoint, and composition at the New Conservatory in Vienna. During the 1920s and 1930s, Kanitz’s works were performed at the Salzburg Festival, as well as in Germany, Rotterdam, and Paris. They were also frequently broadcast, notably on Radio Wien. But Kanitz was best known as the director of the Wiener Frauen-Kammerchor (Vienna Women’s Chamber Choir), which he founded in 1930. The choir performed at the Musikverein in Vienna as well as in Budapest, Brno, and Paris, building a large and enthusiastic audience. The choir’s varied programs included works by Kodály, Honegger, and Stravinsky, as well as compositions and arrangements by Kanitz himself. His status was recognized in 1933 when he joined the board of directors of the Association of Austrian Composers.

Although he converted to Christianity in 1914, his Jewish origins forced him to flee Vienna after Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany. In early June 1938, the Kanitz family left for the Netherlands. They boarded the SS Veendam in Rotterdam and disembarked in Hoboken, New Jersey, on July 26, their immigration being supported by the American Committee for Christian Refugees. After a brief stay in New York, Kanitz and his wife Gertrude settled in Rock Hill, South Carolina, where he obtained a teaching position. After Gertrude’s untimely death from cancer, Kanitz moved to California, where he had a distinguished teaching career at the University of Southern California (USC). There he met composer Ernst Toch, also of Viennese Jewish origin, who became a close friend.

In 1960, his retirement from USC left him much more time for composition, although he continued to teach and give lectures. The 1960s were marked by a series of notable successes. His Bassoon Concerto (1962), premiered in April 1964 by the San Francisco Symphony under Josef Krips, was subsequently programmed by Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra, as well as by Zubin Mehta and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Sinfonia Seria (1963), Kanitz’s first symphony, was premiered by the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Eleazar de Carvalho in October 1964, and his Second Symphony (1965) by Josef Krips and the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra in December 1968. In the 1970s, his teaching and composing career gradually slowed as his health and eyesight deteriorated. Kanitz died in Menlo Park, California, on April 7, 1978, and was buried alongside Gertrud in Due West, South Carolina.

After his death, his music—which includes more than forty works for vocal ensemble, chamber music, chamber opera, and various orchestral formations—fell into oblivion, like that of so many other exiled composers.

Sources: © 2025 Simon Wynberg – Press release and CD booklet of Chamber Works by Ernest Kanitz

Order the CDs Music in Exile

Lear more about the ARC Ensemble