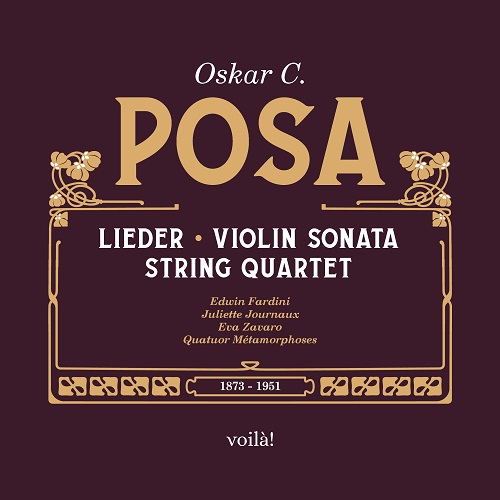

Book and CD set, 2 CDs, 264 pages, published by Voilà Records, September 2025

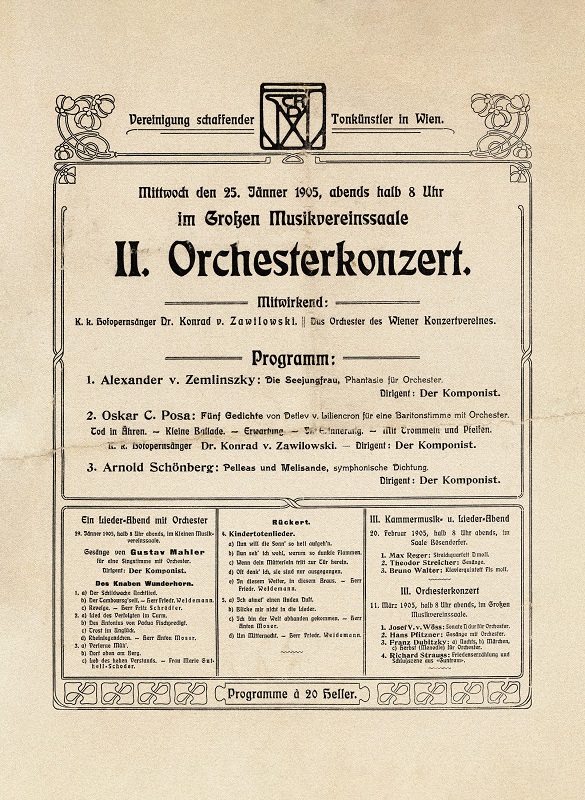

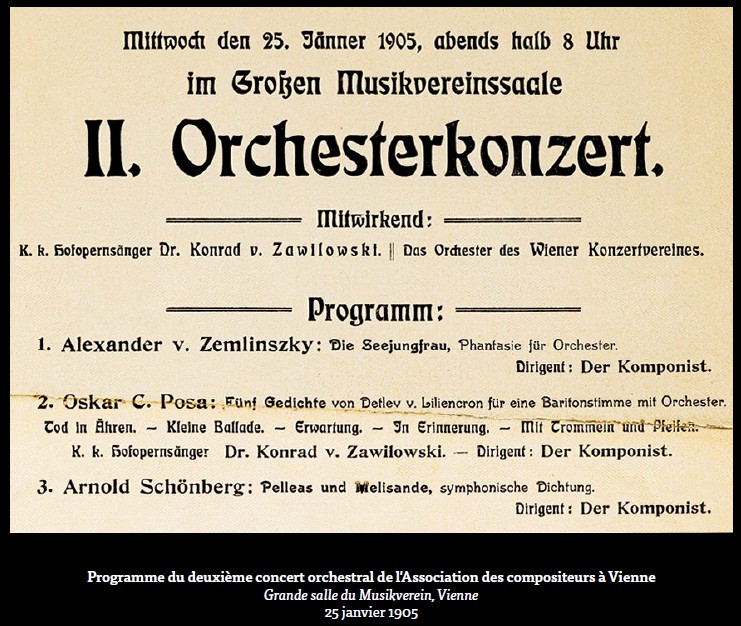

Olivier Lalane’s research began in 2020, during the lockdown. While poring over a poster for a 1905 concert at the Musikverein in Vienna, which he had stumbled upon by chance, he discovered the name of Oskar C. Posa, unknown to the program, flanked by two much more famous composers: Arnold Schönberg and Alexander von Zemlinsky. Intrigued, he searched in vain for Posa’s name on the Internet and in music dictionaries. His curiosity turned into obsession. He then embarked on four long years of research that led him to find scores, manuscripts, and traces of this composer who had fallen into oblivion.

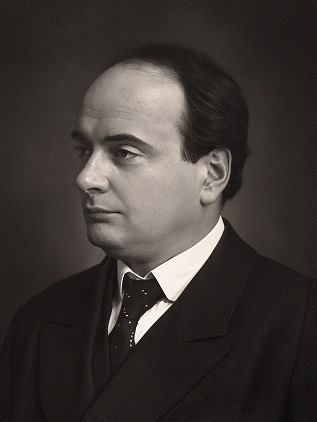

But who was Oskar Posa? His complete obscurity is one of the greatest mysteries in the history of music. A famous post-Romantic Austrian composer at the turn of the 20th century and friend to the great composers of his time, he wrote 80 lieder[1]poems set to music that were sung throughout Europe and the United States. These pieces captivate listeners with their harmonic sensuality, inherited from Brahms and Wagner, and the unprecedented prominence given to the piano, which is on equal footing with the vocals.

Oskar Posa, the tragically ordinary story of a composer who fell victim to anti-Semitism

Born into a Jewish family in Vienna on January 16, 1873, Oskar Carl Posamentir soon abandoned his surname, which was linked to the profession of trimming maker—a craftsman who weaves pom-poms, ribbons, braids, strings, and curtain fringes—and it was under the name Oskar C. Posa that the composer signed his works and appeared on stage at the beginning of his career, until he officially adopted it in the civil registry in 1911. A virtuoso pianist, he took private piano and composition lessons from Otto Bach, Ignaz Brüllet, and above all Robert Fuchs, the harmony and counterpoint teacher of an entire generation of post-Romantic composers, including Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, Hugo Wolf, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Franz Schreker, Jean Sibelius, Max Steiner, and Erich Korngold.

Like Mahler, Posa converted to Catholicism in 1897 in order to pursue a musical career. The Viennese public discovered his music in February 1898, in a concert by baritone Eduard Gärtner and violinist Fritz Kreisler, accompanied by the composer on piano. Four of his lieder were premiered: Heimweh, Heimkehr, Scheiden und Meiden, and Irmelin Rose.

The following year proved decisive. Pianist and composer Julius Röntgen, to whom Posa had sent his scores, fell in love with his music at first sight, writing to him on June 18, 1899: “I rank your lieder among the best ever written, and I am certain that once they become known, this judgment will be universally confirmed. “[2]This reference, as well as much of this article, come from Olivier Lalane’s remarkable booklet accompanying this double album.

The year 1900 began under the best of circumstances: in January, Röntgen and the singer Messchaert performed several of Posa’s lieder in Amsterdam, then in Vienna. They were an instant success. Simrock, Brahms’s long-standing publisher, decided to publish two books of Posa’s lieder. In the second half of 1900, Posa resigned from his position as an assessor at the Vienna District Court to devote himself fully to music.

In 1901, when his genius Violin and Piano Sonata, a work of superhuman difficulty, was due to be performed, the planned performers withdrew at the last minute and the public premiere of the work turned into a nightmare. The composer then sank into a deep depression.

In early 1904, Schönberg, Zemlinski, and Posa decided to found the Association of Composers in Vienna (Vereinigung Schaffender Tonkünstler in Wien), whose mission was to promote modern musical works through concerts. The association’s honorary president was Gustav Mahler, and its members included such prestigious figures as Max Reger, Hans Pfitzner, Max von Schillings, Karl Weigl, Siegmund von Hausegger, Röntgen, and Jean Sibelius. The Vereinigung called on composers to submit new works to be performed in concert. By the end of September 1904, 127 composers had submitted nearly 900 works! The first season promised to be ambitious, with six concerts scheduled. On November 23, 1904, the first concert featured Siegmund von Hausegger’s Dionysiac Fantasy conducted by Zemlinsky, three orchestral lieder by Hermann Bischoff conducted by the composer, and, after the intermission, the Viennese premiere of Richard Strauss’s Sinfonia Domestica, conducted by Mahler.

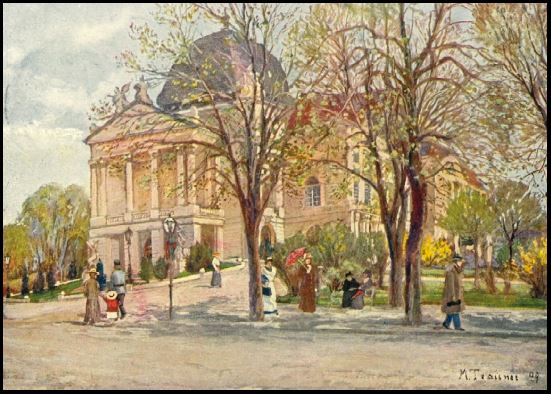

The programme for the second concert, on June 25, 1905, featured three world premieres conducted by their composers: Schoenberg’s Pelleas und Melisande, Zemlinsky’s The Little Mermaid and, in between, Posa’s five Soldatenlieder. The works by Zemlinsky and Posa were relatively well received, but Schoenberg’s complex and lengthy work (nearly an hour long) baffled part of the audience. However, in the conservative Vienna of the early 20th century, none of the three composers escaped the numerous criticisms that appeared in the music reviews after the concert. Posa’s Soldatenlieder suffered from the controversy and were even sometimes ignored!

The association’s third symphony concert, scheduled for March, had to be canceled due to lack of funds and was replaced by a recital of lieder. The Vereinigung, barely established, buckled under the weight of its ambition. Despite donations, revenue, and membership fees, its inevitable dissolution was finalized in the fall of 1905 after a single season of eleven concerts. But for Posa, the mission was accomplished. A financial deficit did not mean an ideological failure. And even if not all of the concerts revealed masterpieces, the association succeeded in introducing names that were still unknown to the general public in Vienna.

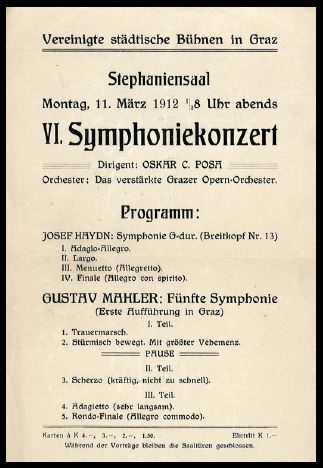

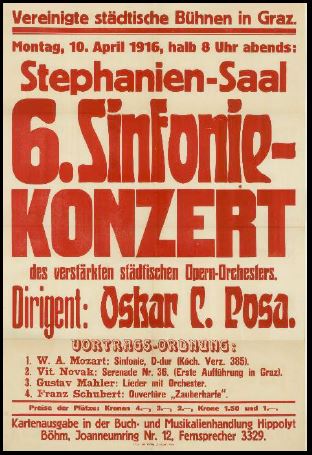

In order to earn a living, Posa became a conductor or choir director at various institutions in Germany and Austria. He also gave private lessons and accompanied singers at concerts. At the same time, he continued to compose lieder, which enjoyed growing success, and in 1911 he found a new publisher, Julius Heinrich Zimmermann, in Leipzig.

That same year, Posa became conductor of Austria’s second largest opera house in Graz, where he performed fairly regularly until 1933. Between 1933 and 1938, he taught as a vocal coach at the prestigious Vienna Conservatory. But on March 11, 1938, Hitler’s troops annexed Austria to Nazi Germany. Four days later, on March 15, Alfred Orel was appointed interim director of the Vienna Conservatory. A Brucknerian musicologist and staunch nationalist, he was tasked with bringing the institution into line with Reich principles: removing Jewish professors or those deemed politically undesirable. On April 7, Posa was suspended from his teaching duties. His permanent dismissal was announced on June 1, 1938. From that day on, his music would never be played again. The composer remained in Vienna without a job, without income, and without the means to leave the country. He shut himself away at home with his sisters Charlotte and Helene. His third sister, Elsa, would soon be deported with her husband Ernst Khuner to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, from which they would escape.

From 1939 onwards, the Nazi regime entrusted musicologist Herbert Gerigk with compiling a Lexicon of Jews in Music, with the aim of excluding them from musical life. Against all odds, Posa did not appear in the first edition published in 1940. On January 11, 1941, a letter signed by a certain Bury, a member of the Nazi Party’s Central Office for Ideological Training, was sent to the dictionary’s publisher. The letter pointed out several omissions that needed to be corrected urgently, including Posa. A few months later, his name was indeed added to the second edition. This official listing among undesirable personalities sealed his definitive exclusion from musical life.

Upon liberation, Posa, then aged 72, was not reinstated at the Vienna Conservatory. Exhausted and penniless, Posa returned to composing in 1947. This period saw the creation of his last three works, which were never published: Edward and Ein Lied Chastelards, two lieder for baritone and small orchestra, the String Quartet, Op. 18, and his only major symphonic work for orchestra, now lost, Praeludium und Fuga fantastica, Op. 19. But Posa could no longer even afford to pay his membership fees to the AKM, the Austrian copyright management society, which deprived him of any possibility of receiving royalties or applying for emergency funds. He died on March 15, 1951, amid general indifference.

Between his death and his funeral, Vienna woke up at the last minute and suddenly remembered his past fame. In recognition of his contribution to the city’s musical life, he was given a grave of honor at the Zentralfriedhof, Vienna’s central cemetery, where Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Wolf, Zemlinsky, and Schoenberg are also resting. His scores and manuscripts were added to the shelves of the Vienna Library, located in City Hall.

Sources: Olivier Lalane, CD booklet Oskar C. Posa (1873-1951) – Lieder, Violin Sonata, String quartet

The interpreters

Juliette Journaux, pianist; Edwin Fardini, baritone; Eva Zavaro, violinist; Quatuor Métamorphoses; Simon Dechambre, cellist

A few words about the Voilà Records label

Founded in 2025 by Olivier Lalane, Voilà Records is dedicated to rediscovering composers who have fallen into obscurity. Each project is conceived as a genuine investigation: digging through library archives, reading, genealogy, hunting for scores, combing through old newspapers. The goal? To bring previously unheard musical treasures out of the shadows and share them with today’s audiences with the same care, if not more, than the great classics.

Order the double album Oskar C. Posa (1873-1951) – Lieder, Violin Sonata, String Quartet