A historic, liturgic and musicologic analysis of the music of the Beta Israel, inspired from the works by Simha Arom, Frank Alvarez-Pereyre, Shoshana Ben-Dor and Olivier Tourny.

It is in the early 1980’s that started the clandestine immigration of Ethiopian Jews to Israel. The latter, improperly called Falasha (pejorative word which means “rootless” or “exiled”) fled, like many of their compatriots, civil war and famine and took refuge in Sudan. In 1984, the operation Moses organized by the state of Israel, allowed to welcome 7.000 Ethiopian Jews coming from the transit camps in Sudan; shortly after, the Operation Saba (1985) repatriated 648 people; finally, the Operation Salomon succeeded in bringing by airlift 14.300 people in 24 hours.

The last Beta Israel who stayed in Ethiopia emigrated to Israel between 1991 and 1994. But in 1992 an irregular emigration began, due to the political evolution in Israel, the Falash Mura. Between 1992 and 2013, over 35.000 Falash Mura arrived in Israel. Officially not Jewish, once in Israel, they had to start a complete conversion to orthodox judaism before obtaining full citizenship.

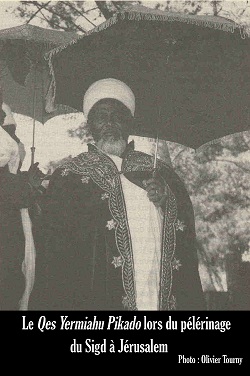

Moreover, under the pressure of Israeli religious authorities, they had to abandon their ancestral ritual practices to belong to a normalised judaism. The Great Rabbinate even tried to force them a symbolic conversion (ritual immersion, and for the men, a “recircumcision” by spilling a drop of blood), that was boycotted by most of them. Recognized today as full-blown Jews, the religious situation of the Beta Israel remains complicated. Their priests, called qessotch, got their religious and spiritual authority taken away… with the consequence of the progressive but inevitable disappearance of their rite.

The Ethiopian community living in Israel numbered around 138,200 people in 2014. Nearly 30,000 children were born into the Jewish state and followed the Israeli educative curriculum. They speak Hebrew and practice the language of their ancestors less and less. The integration process started and the days of Ethiopian ritual, and of its music, are counted.

A few notions about the liturgical music of the Beta Israel [1]Excerpt of the book by Hervé Roten, Musiques liturgiques juives : parcours et escales, Coll. Musiques du monde, Cité de la Musique / Actes Sud, 1998, pp. 107-115

“ The Ethiopian liturgy is composed of spoken and sung prayers, mainly in ge’ez language – a sacred idiom, known only by the initiated. The liturgical chants are led by a priest, a true soloist, who is responded by a choir of the other priests. The soloist – traditionally the highest religious authority of the assembly – starts the prayer ; the others answer uniting their voices. (…) The response of the choir leads to an “archaic” polyphony which appears by the encounter of several voices aiming to produce a one and only melody. (…)

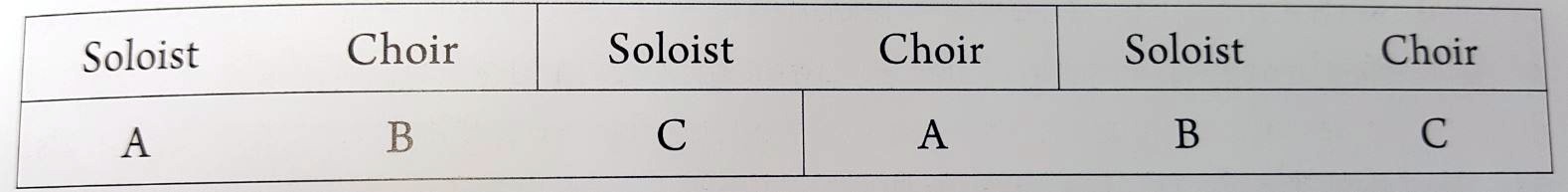

The chants can have different forms. The antiphonal and responsorial forms are frequently used. In a chant of antiphonal type, the choir always repeats the musical tune of the soloist. In a responsorial chant, the choir takes a part of the soloist’s musical material to enounce short responses like “Amen” or “Alleluia”. One can also find a third type of chant that Simha Arom and Olivier Tourny qualify as “hemiola type”. The prayers of this category are characterised by a ternary distribution of the text and music, but in which the binary alternation remains. (…)

Another peculiarity of the Beta Israel’s liturgy is that the modalities of performance of the prayers is not established in advance. Depending on the circumstances, a same chant can be hemiola, antiphonal or responsorial. It is the soloist who, by singing first the chant, decides which configuration it will be. In the case of solemn events, the priests use more the hemiola chants. When they are in a rush, they generally use a responsorial type of chants, which permits to accelerate the flow rate of the text, alternating different verses each time. On the contrary, when they welcome an important religious figure, the priests honour their host by strictly repeating the textual and musical expositions, following the antiphonal form.

Sometimes, the chanting is accompanied by a drum (nagarit) or a small metallic gong (metke). However, the role of these instruments remains secondary due to their prohibition on certain important holidays. (…)

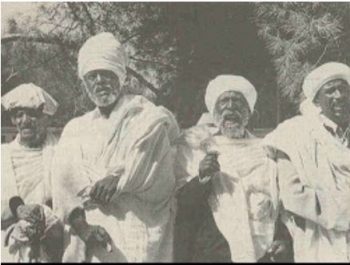

The majority of the chants do not follow any regular metric structure. They are regulated by the prosody of the language. Only certain prayers, associated to dancing, are really measured. In Ethiopia, the dancing is performed by all the priests. It consists of a circular or semi-circular collective movement ; in this last case the qessotch perform rhythmed movements on the spot. They are accompanied by the feet hitting on the floor, and sometimes rhythmed panting. (…)

The chants use mainly a pentatonic and anhemitonic scale (a scale composed of five sounds, each of them distant of at least one tone of his neighbor). A few rare prayers are performed on a tetratonic scale (four sounds). The pitch of the sounds is more or less stable ; it can vary of a half-tone, or more. In fact, the general outline of the melody predominate on the absolute pitch of the degrees and the size of the intervals.

The liturgical music of the Ethiopian Jews is composed of a limited number of melodic formulas which circulate through all the chants. These formulas, generally built upon joint degrees, can present varied profiles; however their global melodic outline remains easily recognizable. In definitive summary, the Ethiopian Jewish music is mainly built on formulas, and regulated by the principle of centonisation. This method – which consists of creating pieces from the arrangement, different each time, of a same stock of melodic formulas – is one of the characteristics of Jewish liturgical music.”

Learn more on the story of Beta Israel

Read the article on the CD boxset The Liturgy of Beta Israel

Listen to the radio podcast by Olivier Tourny about the liturgical chanting of Ethiopian Jews (in French)

Listen to the playlist The musical traditions of Ethiopian Jews

| 1 | Excerpt of the book by Hervé Roten, Musiques liturgiques juives : parcours et escales, Coll. Musiques du monde, Cité de la Musique / Actes Sud, 1998, pp. 107-115 |

|---|