By Hervé Roten

The status of women in the Jewish tradition is often source of controversy. The halakha – the Jewish law – generally puts the woman in the role of the housekeeper, educator of her children. But it has not always been like that.

When we look back at the Book of Judges that tells us the story of the Hebrews, between the conquest of Canaan and the arrival of royalty, one woman has a special place. It’s Deborah, 4th judge of Israel, prophetess and military chief. In the 13th century before J.C., she convokes a warrior named Barak so that he builds an army among the tribes of Naphtali and Zebulun to defeat the Canaanite army of Sisera who serves king Jabin. After a ferocious fight, Sisera is killed by another woman, Jael. And this victory leads to the final defeat of canaanite king Jabin. Deborah sings then with Barack a hymn, a victory song that echoes like a warning to foreign princes and kings that can be a menace to the Hebrews.

Through this Biblical tale is the image of a freed and liberator woman, equal to man, who doesn’t hesitate to sing with him. Another reference to the singing of woman takes place after the crossing of the Red Sea. The men sing a hymn to God (Chirat hayam) then Myriam, sister of Moses, and all the women dance to the sound of the tambourine after that the waters of the Red Sea have swallowed the Egyptians (Exodus, XV, 20). At that moment, men and women are symbolically unified by singing.

This will not prevent the Rabbis to decree centuries later the singing of women as impure. The voice expresses the nudity, and the halakha says a woman must not sing in presence of men, to not distract them from prayer and study.

This is why for a long time, women sang mainly inside the house (lighting of Shabbat candles, lullabies, entertainment songs…) or during special occasions (marriages, funerals…).

It’s in the middle of the 18th century, with the birth of the Haskala – the Jewish Enlightenment – that will appear great changes in Judaism. Women can then have access to an education based on the foundations of Western general culture.

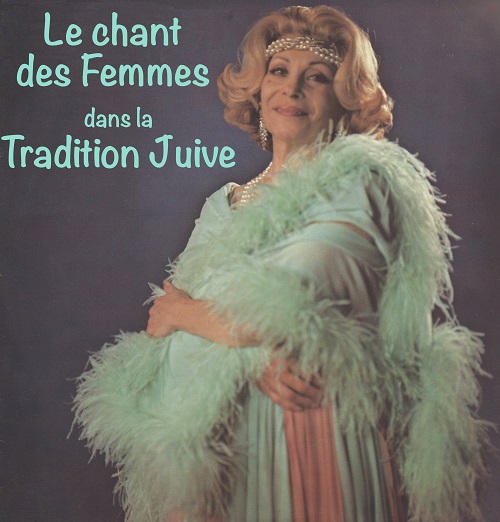

Nowadays women sing in multiple ways according to the level of religiousness. In orthodox circles, they have to strictly follow the Halakha. In traditionalist circles, women sing along with men. Among the reformed, women sing freely, some of them are hazzanit (feminine word for hazan that means cantor). Finally, among the non-religious Jews, but very attached to their Jewish identity, the singing has become symbolically a high mean of identity, which explains the renewed interest for Yiddish, Judeo-Spanish and Arabic songs, sang by men and women.

Listen to the radio program : The Judeo-Spanish singing by women from Morocco

Learn more on the CD of Naïma Chemoul (Maayan) : From Andalucia to the Orient… The singing of Sefardi women